Posted on 01st July, 2024

The Madness of King Ludwig

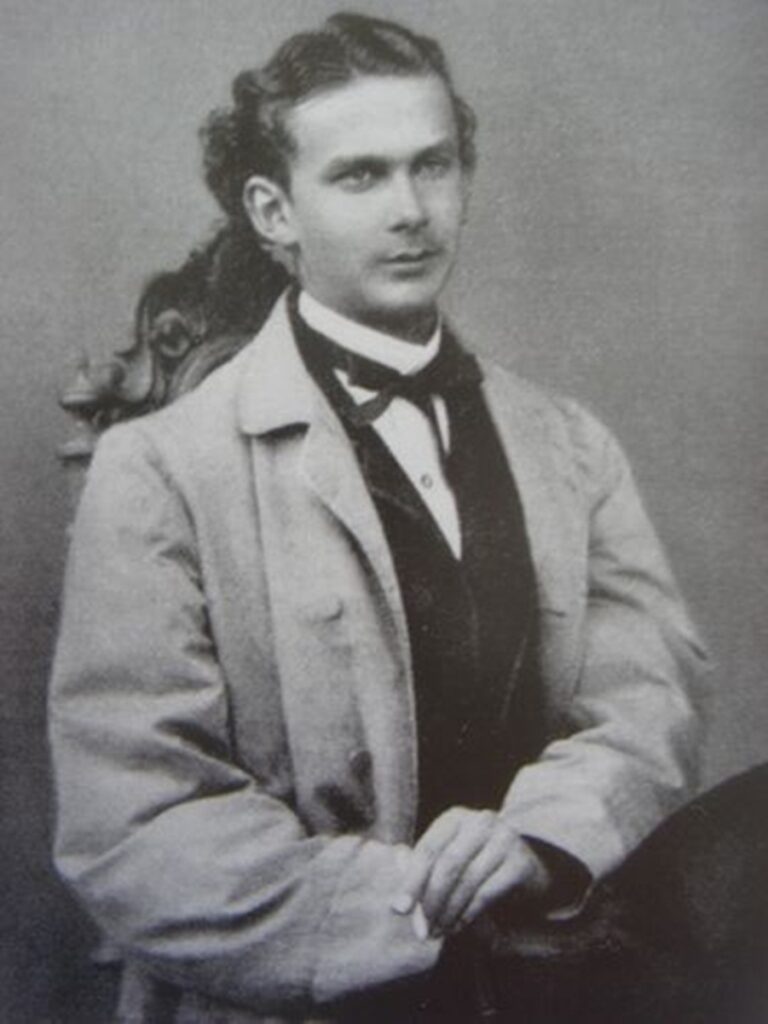

King Ludwig II of Bavaria was one of the most complex, fascinating characters in history. When discussing him, it has become almost obligatory to give him the prefix “Mad”. But is that accurate, or fair?

There was certainly mental instability in his family. On his mother’s side, there were ancestors who had suffered from hallucinations, and on his father’s side, his Aunt Alexandra spent years in a mental institution, convinced that she’d swallowed a glass piano. His younger brother, Otto, was certified insane when he was only in his twenties, and spent the rest of his life in some kind of secure confinement, but what about Ludwig?

He came to the throne of Bavaria in 1864, at the age of 18, after his father Maximilian’s sudden and unexpected death. Immature and ill-prepared, he wasn’t ready for ruling, but nevertheless applied himself to his royal duties conscientiously – at least, at the beginning. Very soon, however, he became bored with politics and ministerial meetings, particularly after the Austro-Prussian War of 1866, in which Bavaria sided with the losing Austrians and, as a result, had to cede a lot of its independence to Bismarck’s Prussia.

Already limited in his powers by the Bavarian constitution – much to his frustration as he wanted to be an absolute monarch like his hero Louis XIVth of France – Ludwig started to withdraw from the real world into a fantasy realm where he could indulge his eccentric whims.

He stopped meeting his ministers, stopped going out in public, even to the theatre which had once been his passion. He turned his days upside down, living a strange nocturnal existence where he had his breakfast in the evening, his lunch in the middle of the night and his supper in the morning. And his household had to keep the same hours to accommodate him.

He took to going out at night on carriage or – in winter – sleigh rides through the countryside on which he would stop at villages and shower the bewildered villagers with gifts. They, of course, had no idea who he was as he generally dressed in a coat and bowler hat and looked nothing like the common image of a king. (One of his sleighs is on display in the museum at the Nymphenburg Palace in Munich. It’s a magnificent vehicle with a golden mermaid at the front, holding aloft two lanterns powered by an electric battery hidden under the seat – pretty advanced technology for its time)

His behaviour became unpredictable, particularly in his treatment of his servants or other palace personnel. A cavalryman celebrating his birthday suddenly found himself summoned into the king’s presence and presented with cigars, bottles of wine and cakes. An infantryman, standing guard in the grounds of Nymphenburg, was perceived by Ludwig to be looking a little tired so the king ordered a sofa to be brought out of the palace for the poor fellow to lie down on. (You can imagine the ribbing the soldier got when he returned to barracks at the end of his shift!)

But on other occasions, Ludwig would be aggressive and violent towards his servants, kicking them or even emptying wash basins over their heads when they displeased him. Sometimes he was so incensed that he ordered servants to be flogged, imprisoned or executed – punishments which, fortunately, were never carried out.

Once, he invited his favourite grey mare to dinner and served her food on the finest Sèvres porcelain, which the horse licked clean and then proceeded to smash with her hooves. Other dinner guests were entirely imaginary. Ludwig would have the table set with extra places for Louis XIVth and his wife, Madame de Maintenon, and chat to them enthusiastically throughout the meal.

More controversial was the king’s obsession with building palaces. When he came to the throne, he already had several, notably Nymphenburg and the Residenz in Munich, and Hohenschwangau in the Bavarian Alps. But those were his father’s palaces. Ludwig wanted his own. So he started building, first at Linderhof near Oberammergau, then Neu Hohenschwangau (later renamed Schloss Neuschwanstein) on a crag near the existing palace, then Herrenchiemsee on an island in a lake where he planned a “mini-Versailles” as magnificent as Louis XIVth’s original.

Was this all evidence of insanity, or just the indulgent behaviour of a monarch with a fertile imagination – and an ingrained sense of entitlement – who could do what he pleased? Or thought he could, anyway.

His ministers certainly weren’t happy with Ludwig. They were alarmed by his increasingly erratic behaviour and the debts he was incurring through these extravagant building projects. Unable to rein him in, they started to plot to get rid of him.

Evidence against him was collected – from ministers, servants and other members of the royal entourage, many of whom were hostile towards the king – and presented to Dr Bernhard von Gudden, the distinguished Munich psychiatrist who had certified Ludwig’s brother, Otto, insane. Without even examining the king, von Gudden declared him insane and unfit to rule.

By this point, Ludwig’s uncle, Luitpold, had already been lined up to take over from him. The Bavarian government appointed him regent and Ludwig was taken by force from Neu Hohenschwangau to Berg Castle, near Munich, where he was locked up under the watchful eye of von Gudden and his assistants. Two days later, the king was dead.

What happened? No spoilers here, but my novel The Wolves of Nifelheim might shed some light on the mystery.